“Their sons grow suicidally beautiful At the beginning of October, And gallop terribly against each other’s bodies.” ~ Excerpt from Autumn Begins in Martins Ferry, Ohio by James Wright (1963)

“It's a mild form of massacre, but the victims seemingly don't mind at all. [These young men] many of them former high school football players … can't resist the desire to knock noggins again... That's sandlot football!” ~Wheeling News-Register Sportswriter Arnold Lazarus (1954)

Modern football fans are quite familiar with the risks players assume, having learned of the brain trauma that drove Mike Webster and so many others to madness and early death, and having witnessed on national television terrifying injuries to players like Darryl Stingley, Ryan Shazier, and Damar Hamlin, among others. And the efficacy of resulting equipment safety innovations will only be revealed with time.

Yet still we watch.

But as risky as the modern game can be, imagine playing a more lawless brand of football in just a sweater and perhaps a thin leather helmet, or no helmet at all, while dubious or non-existent rules enabled deliberately malicious “scrimmages” or plays – strategies designed to mangle and maul for the all-important goal. Nascent sandlot football was indeed a form of massacre, and not at all a mild one. And despite the violence, its popularity in the Upper Ohio Valley seldom waned. Long before the Wheeling Ironmen and even before the Pittsburgh Steelers, local sports fans turned out to watch a brutal brand of Ohio Valley football featuring teams with names like the Yankees, Tigers, Vigilants, Staats, Trussels, Bearcats, Bulldogs, Mohawks, Olympics, and Columbias. Horrific injuries were common. Deaths were not uncommon. This was gladiatorial combat with arms and feet as bludgeons and battle axes, torsos as battering rams, and course heads of hair or paltry scraps of leather as woefully inadequate shields.

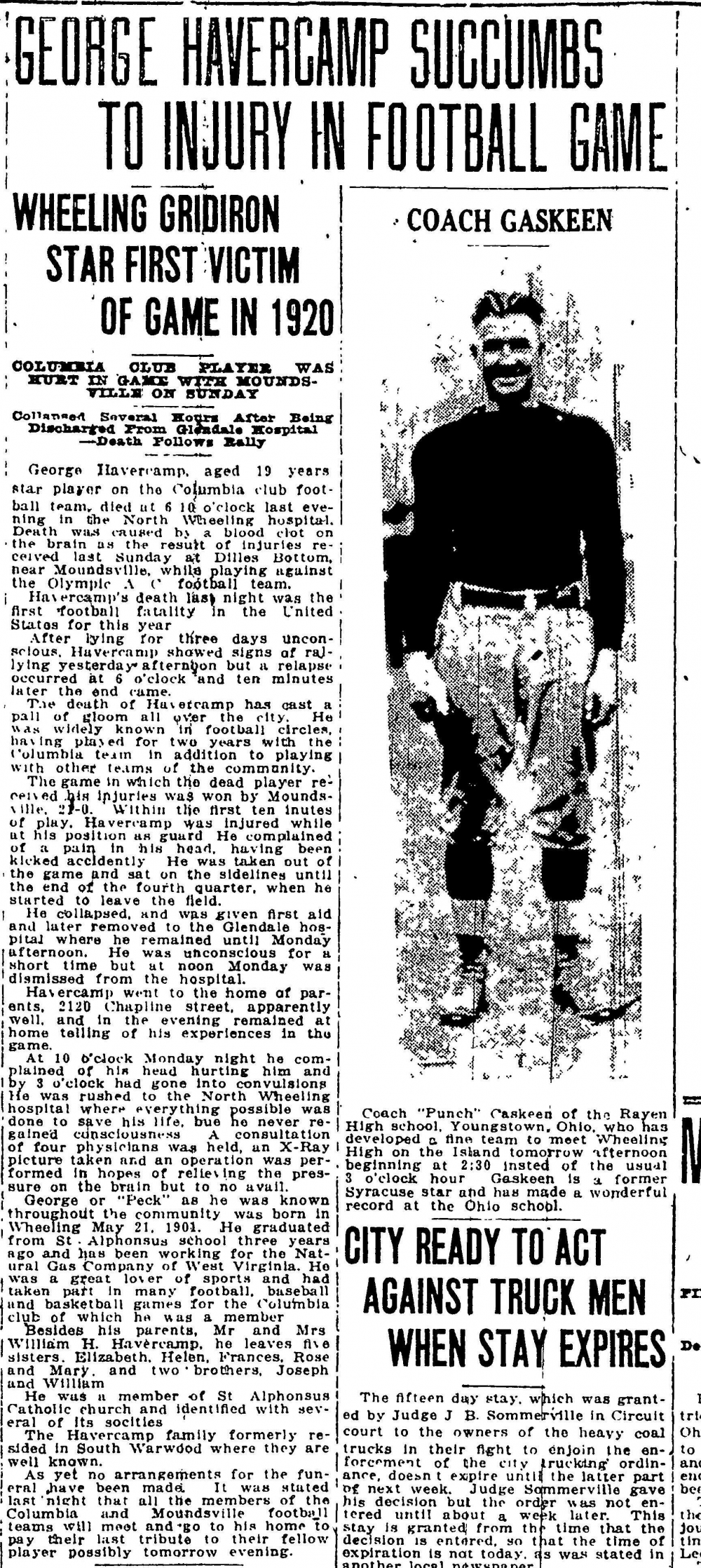

One local contest that would live in infamy took place on Sunday, September 26, 1920, an unseasonably warm day for late summer football. (1) The well-established Columbia Athletic Club of South Wheeling had accepted a challenge to travel to Fort Pitt field across the Ohio River from Moundsville to take on that town’s brand new football eleven, known as the Olympics. (2) Early in the first half of the first game of the season for both squads, Wheeling’s star guard George “Happy” Havercamp ran to the sideline complaining of a headache, saying he had bumped his head. After seizing and lapsing into unconsciousness, Havercamp and was carted off to the Glendale Hospital under the care of a physician in attendance. (3) Adding insult to injury, the newbie Olympics won the game 21-0. It was later determined that Havercamp had been accidentally kicked in the back of the head near the base of his skull. Since no fractures were found, his early prognosis was optimistic, and he was released from the hospital the following day. But, just one day later, after more convulsions, hemorrhaging, and another loss of consciousness, the young man was admitted to Wheeling Hospital, then located in North Wheeling. Havercamp was diagnosed with a blood clot, and his condition declined rapidly. Despite a team of doctors and emergency surgery to relieve the pressure on his brain, Havercamp never regained consciousness. He passed on Thursday, September 31, 1920. (4) After a funeral Mass at St. Alphonsus with his teammates as pallbearers, Havercamp was interned at Mt. Calvary. (5) Originally from Warwood, George Havercamp lived on Eoff Street in Centre Wheeling and worked for the gas company. He was 19 years old. According to the Intelligencer, his was the first football death in the country for that year, and “cast a pall of gloom over the city.” (6)

One local contest that would live in infamy took place on Sunday, September 26, 1920, an unseasonably warm day for late summer football. (1) The well-established Columbia Athletic Club of South Wheeling had accepted a challenge to travel to Fort Pitt field across the Ohio River from Moundsville to take on that town’s brand new football eleven, known as the Olympics. (2) Early in the first half of the first game of the season for both squads, Wheeling’s star guard George “Happy” Havercamp ran to the sideline complaining of a headache, saying he had bumped his head. After seizing and lapsing into unconsciousness, Havercamp and was carted off to the Glendale Hospital under the care of a physician in attendance. (3) Adding insult to injury, the newbie Olympics won the game 21-0. It was later determined that Havercamp had been accidentally kicked in the back of the head near the base of his skull. Since no fractures were found, his early prognosis was optimistic, and he was released from the hospital the following day. But, just one day later, after more convulsions, hemorrhaging, and another loss of consciousness, the young man was admitted to Wheeling Hospital, then located in North Wheeling. Havercamp was diagnosed with a blood clot, and his condition declined rapidly. Despite a team of doctors and emergency surgery to relieve the pressure on his brain, Havercamp never regained consciousness. He passed on Thursday, September 31, 1920. (4) After a funeral Mass at St. Alphonsus with his teammates as pallbearers, Havercamp was interned at Mt. Calvary. (5) Originally from Warwood, George Havercamp lived on Eoff Street in Centre Wheeling and worked for the gas company. He was 19 years old. According to the Intelligencer, his was the first football death in the country for that year, and “cast a pall of gloom over the city.” (6)

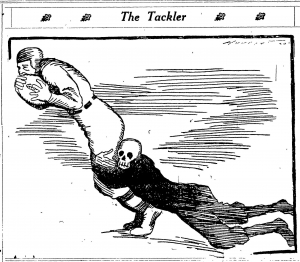

But Havercamp’s sad fate was just a relatively obscure footnote in the national story of carnage that was early sandlot football, where the reaper lurked in every corner of the gridiron.

But how and why did this new and growing athletic obsession become so violent?

The first game of what is now considered to have been “American Football,” (or Foot Ball, as it was spelled then) a game that evolved from the brute force of rugby combined with the finesse of soccer, was played on November 6, 1869, in New Brunswick, New Jersey, between Princeton and Rutgers, with the latter prevailing 6 to 4. (7) The rules were based on those of the “London Football Association,” with now alien concepts like 25 players to a side all trying to kick or head butt the ball. Carrying the ball was prohibited. Each goal was worth one point and the first to six was the winner. This strange new game, which, instead of “Football,” might have been called “Gang Soccer” or “Assault Rugby,” would mutate and evolve wildly over the next century to become what we know today – apologies to baseball – as America’s most popular sport. (8)

The first game of what is now considered to have been “American Football,” (or Foot Ball, as it was spelled then) a game that evolved from the brute force of rugby combined with the finesse of soccer, was played on November 6, 1869, in New Brunswick, New Jersey, between Princeton and Rutgers, with the latter prevailing 6 to 4. (7) The rules were based on those of the “London Football Association,” with now alien concepts like 25 players to a side all trying to kick or head butt the ball. Carrying the ball was prohibited. Each goal was worth one point and the first to six was the winner. This strange new game, which, instead of “Football,” might have been called “Gang Soccer” or “Assault Rugby,” would mutate and evolve wildly over the next century to become what we know today – apologies to baseball – as America’s most popular sport. (8)

At first, the game remained a pastime at elite Ivy League colleges like Princeton, Columbia, Yale, and Harvard, with the latter forcing the next step of the evolution after playing the rough and tumble McGill College of Canada in 1874. American Football would then become something more violent, more like rugby, less like soccer. For this reason, Canada can be credited (or blamed) as a pioneer in the game’s development. (9)

During the early battles between Harvard and Yale in 1875 and 1876, a Yale student athlete named Walter Camp emerged, and would later become known as “The Father of American Football.” His rule innovations included 11 players to a side and, most importantly, the 1880 concept of possession, which differentiated the game most starkly from rugby. Now, instead of a continuous fight for possession, a quarterback would take the ball from a “snapback” (center) and pitch it, generally to a halfback. (10)

One of the major problems with the early rules was the so-called “block game,” which resulted from teams trying not to lose. As there was no penalty for ending up in your own end zone repeatedly, a team could effectively possess the ball and block the other team from scoring in an entire half by not trying to score themselves. The opponent would often do the same in the second half. The result was a tedious gridiron wrestling match ending most often in zero-zero ties. Something had to give. (11)

The Intercollegiate Association’s solution was to pass a “down and yards to gain rule” (1882), which ushered in what we now know as the “gridiron.” The game was starting to look familiar. (12) Early scoring rules remained bizarre and confusing until numerical scoring was passed in 1883. Eventually, a touchdown came to be superior to a kicked goal from the field.

But the next two steps in the game’s evolution would increase the risk to player health exponentially. (13)

Tackling below the waist was illegal in rugby, as was “creating interference” or blocking for a ball carrier. The ball had to be ahead of the other players or offsides was called. American football officials made both maneuvers legal in 1888, forever changing the game.

The strategies these two innovations would enable – so called “mass momentum” plays – would make playing football one of America’s number one health risks. (14)

Innovated by Princeton, circa 1884, the “V Trick” became the first “mass momentum play” that led to even more dangerous strategies. The idea was to align offensive players in the shape of a V with the ball carrier inside the apex, thereby using the momentum of multiple players (mass) arms locked and focused on one or few players on defense to create a human battering ram in order to force the ball forward. If one is reminded of a modern variation known as the “Brotherly Shove” or the “Tush Push,” one is not far from the old school reality. (15)

Innovated by Princeton, circa 1884, the “V Trick” became the first “mass momentum play” that led to even more dangerous strategies. The idea was to align offensive players in the shape of a V with the ball carrier inside the apex, thereby using the momentum of multiple players (mass) arms locked and focused on one or few players on defense to create a human battering ram in order to force the ball forward. If one is reminded of a modern variation known as the “Brotherly Shove” or the “Tush Push,” one is not far from the old school reality. (15)

Back in the 1880s, some defenders would try to fall to the ground to disrupt the wedge. Others, like Pudge Heffelfinger (who would later become the first man to be paid to play football) would attempt to leap over the wedge and essentially tackle the entire backfield. (16)

In 1890, the Wheeling Register ran a letter by heavyweight boxing champion Jack Dempsey, in which he defended the art of pugilism by comparing it to football. “As to football,” Dempsey wrote, “the newspaper record of injuries received by players on the two foremost college teams shows a larger number of casualties in one match than prize rings all over the country yield in a year.” He wasn’t wrong.

Much like in modern football, other teams saw the success of the V Trick and copied it for their own use, such that it became a common play. By 1892, this simple play had evolved into something far more stunning, potentially lethal, and militaristic, based, as it was, on ancient military strategy to attack a point in the opponent’s line with overwhelming strength, using a triangle, with the ball carrier inside.

Developed by Lorin F. Deland and first used by Harvard in a game against Yale, the “Flying Wedge” added momentum by having the two sides of the V converge by running from opposite sidelines to meet in front of the ball carrier at full speed. Now the battering ram had torque and inertia, creating a powerful, locomotive-like effect that led to numerous injuries and deaths. It was football as the art of war, and there were no rules to prevent this by requiring players to be set. Indeed, Deland credited Napoleon for his innovation, and other teams were soon copying the play. (17)

Developed by Lorin F. Deland and first used by Harvard in a game against Yale, the “Flying Wedge” added momentum by having the two sides of the V converge by running from opposite sidelines to meet in front of the ball carrier at full speed. Now the battering ram had torque and inertia, creating a powerful, locomotive-like effect that led to numerous injuries and deaths. It was football as the art of war, and there were no rules to prevent this by requiring players to be set. Indeed, Deland credited Napoleon for his innovation, and other teams were soon copying the play. (17)

Other mass momentum plays inspired by the Flying Wedge included the “Turtleback,” a semi-circular variation, and the “Push Play” in which the runner was essentially hurled over the line. Football had devolved into an ugly form of micro warfare, and people started to dislike it. Changes to the rules were needed to save the game.

By 1894, momentum plays and piling on were forbidden, the length of games was shortened, and blockers could no longer use their hands to grab or punch opponents. (18)

Long before he was elected president, Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt became an avid fan on American football. His sons played, and he often extolled the virtues of the new manly sport for the valuable life lessons he believed it taught.

Long before he was elected president, Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt became an avid fan on American football. His sons played, and he often extolled the virtues of the new manly sport for the valuable life lessons he believed it taught.

But by 1905, the rugged game was in existential trouble due to excessive violence, injury, death and corruption. According to newspaper reports, 19 to 25 people had died and more than 160 had been seriously injured playing football that season, largely due to legal (or at least not illegal) brutality. A Chicago Tribune headline dubbed the 1905 season, “Football Year’s Death Harvest.” (19)

The game was ugly, and people were losing interest. The president, whose own son Ted had received a badly broken nose as a freshman player at Harvard, knew something had to be done to save the game from itself. Declaring “football is on trial,” he called a summit at the White House and invited influential coaches like Yale’s Walter Camp and William Reid of Harvard, along with Secretary of State Elihu Root, tasking them with deescalating the wanton violence of the game he loved. (20)

After more pressure from Roosvelt in the wake of the summit, rule changes finally passed, including allowing the forward pass, changing the yardage for a first down from five to ten, and creating a neutral zone between the offensive and defensive lines. By the end of that bloody year, the establishment of the Intercollegiate Athletic Association, precursor to the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), allowed for better management of rules and more adjustments for player safety. (21)

But did Teddy Roosevelt actually save football in 1905? There is plenty of evidence to suggest that such was not the case. First and foremost, the game was not, in fact, less deadly. By 1909, there were 26 deaths nationally, one more than there had been in 1905.

Demands for an outright ban were back, and the Intercollegiate Athletic Association met to address the problem, compiling a list of the “twenty most dangerous plays in football,” which included the diving tackle, the kickoff return, striking with the knee, piling on a player crawling with the ball (players with the ball had to yell that they were “down”), intentional fouls, using the heal of a hand on an offensive player’s face (to evade the no punching rule), exhaustion, concentrated and continuous attacking against one player, throwing oneself under a mass of players, uneven matchups, and poor conditioning. Thus, in 1910 the Rules Committee actually did pass rules to improve the safety of the game. (22)

But this still wasn’t enough to save Rudolph Munk.

Readers might be surprised to learn that, beginning in 1894 and ending during the second World War, Bethany College and West Virginia University played fourteen times.

Readers might be surprised to learn that, beginning in 1894 and ending during the second World War, Bethany College and West Virginia University played fourteen times.

Though the modern fan would perceive this to be a lopsided mismatch – and WVU did win all of the games save one (a 0-0 tie in 1910) – many of the final scores were surprisingly close. The first game in 1894, for example, ended 6-0.

The teams played a home and away bill in 1910, which led to the most famous, or rather infamous, result. While the Morgantown game ended in a 0-0 tie, the second game, played on Wheeling Island on Nov. 12 and billed as the “State Championship of West Virginia,” ended with a 9-0 WVU win. But that was not the story. (23)

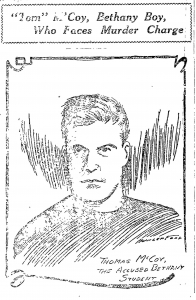

The story was that a WVU player named Rudolph Munk, left halfback and captain, was injured near the end of the game, and later died of a brain bleed at City Hospital. (24) Furthermore, Thomas McCoy, the Bethany player who tackled Munk on the play, was arrested, charged with murder, and later exonerated. (25)

The story was that a WVU player named Rudolph Munk, left halfback and captain, was injured near the end of the game, and later died of a brain bleed at City Hospital. (24) Furthermore, Thomas McCoy, the Bethany player who tackled Munk on the play, was arrested, charged with murder, and later exonerated. (25)

Accounts differ, but McCoy (who was accused of being a paid mercenary) either hit Munk with forearms to the upper body, fists to the back of the neck, or a kick in the head. In any event, the umpire ruled the hit was deliberate and illegal, ejecting McCoy from the game.

At the coroner’s inquest, however, the umpire recanted. As it was also known that Munk had suffered previous head injuries and was thought to have played despite being unwell from an earlier injury, the death was ruled accidental.

Both teams canceled their remaining schedules and McCoy never played football again. (26)

Wheeling’s football story began many years before Munk’s unfortunate death.

One of the earliest local mentions of a game of what we think of as American Football or “Foot Ball” can be found in the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer of November 25, 1882, wherein “the boys propose having a big game of football Thanksgiving afternoon on the commons above the furnace track.” (27) Thus did football become associated with Thanksgiving at an early date. It was, after all, a day off, and the game provided a great way to work up an appetite.

The game’s popularity grew. In 1891, a writer for the Register predicted that “foot-ball” was the game of the day, while “base-ball” was no longer “in-it.” The writer lauded the new game’s combination of “science and muscle” and opined that the “crack base ball player would doubtless be a mere toy in the hands of his football contemporary.” He then correctly noted that Wheeling had “lots of the finest material for making foot-ball players” and then presciently called for the formation of local clubs from “Wheeling, Benwood, Bellaire, Bridgeport, and Martins Ferry.” (28)

On the next page, the Register reported about another Thanksgiving Day game, this one between the local Y.M.C.A. club and a team called the “Beginners,” with the later winning despite their apparent inexperience. Despite the loss, the Y.M.C.A. would take the lead role in the development of football locally. (29)

In general, local teams would form, choose a name, then challenge other neighborhood teams via the newspaper, much like in base-ball during the same period. In 1893, for example, a North Wheeling team comprised of “big strong mill men” challenged the team from Fulton. (30 )

In 1893, football’s popularity in the Valley took off as the “Gym” team from Wheeling (wearing red and white) and the Martins Ferry Y.M.C.A. club (wearing lavender and black) prepared to play a Thanksgiving rivalry game on the Island Fair Grounds (admission 25 cents) with the proceeds benefitting the recently opened City Hospital (later OVGH). “One of the largest crowds ever assembled in this city,” was expected, for what the newspapers were calling “one of the society events of the season.” (31)

In 1893, football’s popularity in the Valley took off as the “Gym” team from Wheeling (wearing red and white) and the Martins Ferry Y.M.C.A. club (wearing lavender and black) prepared to play a Thanksgiving rivalry game on the Island Fair Grounds (admission 25 cents) with the proceeds benefitting the recently opened City Hospital (later OVGH). “One of the largest crowds ever assembled in this city,” was expected, for what the newspapers were calling “one of the society events of the season.” (31)

The first match between another Wheeling team and Ferry that October had ended with Ferry winning, 20-0 as the Wheeling boys reportedly had “less wind and meat” than their opponents (32).

The first match between another Wheeling team and Ferry that October had ended with Ferry winning, 20-0 as the Wheeling boys reportedly had “less wind and meat” than their opponents (32).

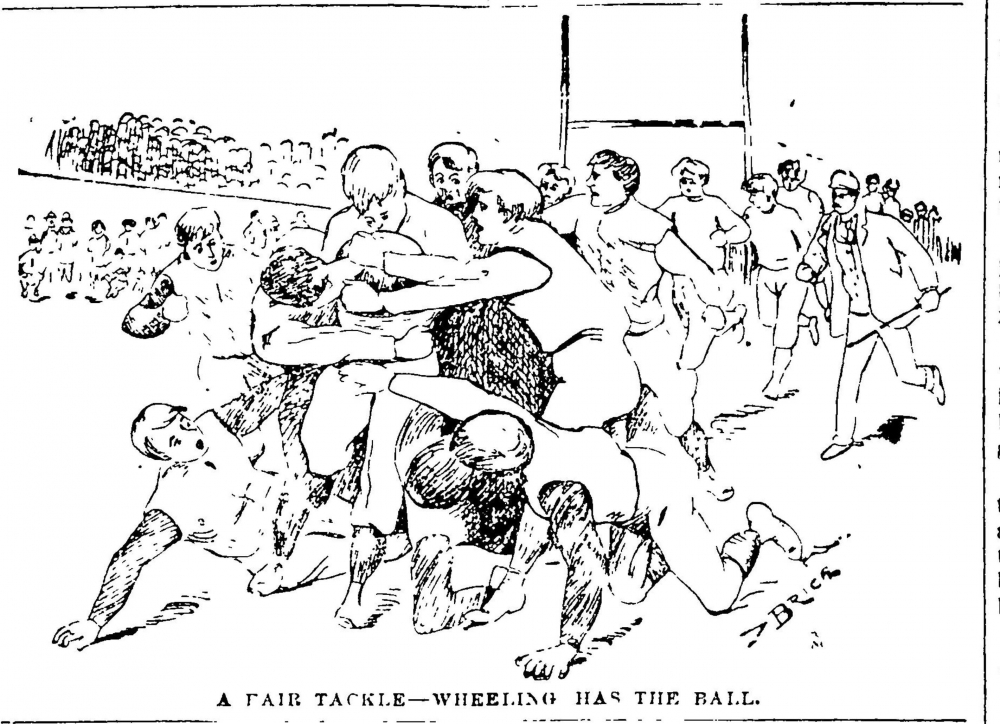

In anticipation of the Thanksgiving match, the Register had run a preparatory article featuring an explanation of the rules and a diagram of the field. In keeping with the old rugby rules still in place at the time, “throttling,” “striking with closed fists,” and tackling “below the hips” were forbidden but the old flying wedge was still in play – Wheeling attempted one or two unsuccessfully against Ferry’s “heavyweight line.” Ferry’s average weight was 166 lbs per man compared to 153 for Wheeling. (33)

Apparently, the Wheeling boys, despite the fact that former college players had been added, had gained neither wind nor meat over the first incarnation, as Ferry again prevailed, 18-0 before a crowd of about 2,000.

Apparently, the Wheeling boys, despite the fact that former college players had been added, had gained neither wind nor meat over the first incarnation, as Ferry again prevailed, 18-0 before a crowd of about 2,000.

The Ferry boosters “rent the air” with cheer “Hi! YI! Y.M.C.A. Boom-de-ay! Rah! Rah!” (34)

The final report on the big game featured a few interesting illustrations.

Names on the Wheeling team included Ziegenfelder (Centre) and Brockunier (FB), while Ferry’s star player was Right End Gjertsen.

While Ferry suffered no injuries,  “several of the local players were badly used up.” One player was kicked in the face and required stitches, while another suffered an “ugly cut” on the head that had to be sewn shut by a surgeon. (35) By the next season, while the Y.M.C.A. team was defeating Franklin College 12 -10 (36),

“several of the local players were badly used up.” One player was kicked in the face and required stitches, while another suffered an “ugly cut” on the head that had to be sewn shut by a surgeon. (35) By the next season, while the Y.M.C.A. team was defeating Franklin College 12 -10 (36),

Martins Ferry fielded another strong sandlot team sponsored by the Vigilant firehouse. That team was rewarded with an oyster supper after a 22 -0 victory over Steubenville. While the junior Vigilants played Linsly to a 0-0 tie, the senior team was strong enough to take on college players from Holy Ghost College in Pittsburgh, while a scheduled game against Washington and Jefferson was postponed due to weather. (37)

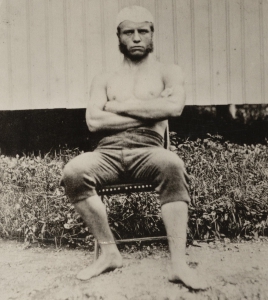

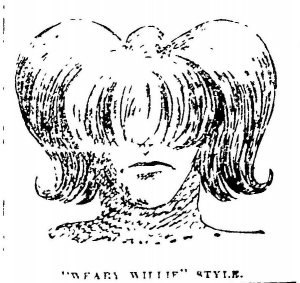

Without even thin leather helmets as a viable option, many college football players of the 1890s chose hirsute helmets, tonsorial towers, and meaty coifs that they hoped would protect their vulnerable craniums from football-induced trauma.

The Register reported on this phenomenon in an October 1, 1893 article headlined, “Long Haired Kickers: Paderewski Out-Paderewskied – Why the Sturdy Football Players of Our Colleges are So Fond of Hair on Their Heads and So Averse to Wearing Any on Their Faces.” Such players would create a great depression for barbers by avoiding haircuts until the hair “curls around his ears; it stands erect upon his head like the quills of a porcupine, it hangs over his collar with the grace that lurks about a half pruned hedged fence, and it mats itself upon his brow like the untutored forelock of a friendless mule.” They would resemble “chrysanthemums after a gale.” Other styles included the “Scotch Terrier,” the “Yorkshire,” the “Pond Lily,” the “American Beauty,” the “Weary Willie,” the “Dish Rag,” and the “Peanut Taffy.” (38)

The Register reported on this phenomenon in an October 1, 1893 article headlined, “Long Haired Kickers: Paderewski Out-Paderewskied – Why the Sturdy Football Players of Our Colleges are So Fond of Hair on Their Heads and So Averse to Wearing Any on Their Faces.” Such players would create a great depression for barbers by avoiding haircuts until the hair “curls around his ears; it stands erect upon his head like the quills of a porcupine, it hangs over his collar with the grace that lurks about a half pruned hedged fence, and it mats itself upon his brow like the untutored forelock of a friendless mule.” They would resemble “chrysanthemums after a gale.” Other styles included the “Scotch Terrier,” the “Yorkshire,” the “Pond Lily,” the “American Beauty,” the “Weary Willie,” the “Dish Rag,” and the “Peanut Taffy.” (38)

And as fond as they were of the long hair, football players were just as adamantly opposed to any facial hair. But, the writer affirmed, “there is method in all this apparent madness.”

And as fond as they were of the long hair, football players were just as adamantly opposed to any facial hair. But, the writer affirmed, “there is method in all this apparent madness.”

The hair served two purposes: it kept the head warm during cold weather games and it kept “together a football player’s brains [as well] as the steel helmet of Richard Lion Hearted’s day.” The only reason cited for the lack of facial hair was that players found the idea of being tackled by their whiskers to be repugnant, but apparently lacked the same kind of concern for their wigs. (39)

In 1895, Edward Barrows formed a new Wheeling powerhouse football team known as the Tigers from remnants of the old Martins Ferry Y.M.C.A. team. (40) The team was comprised in part by “several well-known college men.”

In 1895, Edward Barrows formed a new Wheeling powerhouse football team known as the Tigers from remnants of the old Martins Ferry Y.M.C.A. team. (40) The team was comprised in part by “several well-known college men.”

The four Edwards brothers were the cornerstone as the Intelligencer later gushed: “probably nowhere in the country could one find a single family that produced an equal number of such brilliant players, and for many years the name Edwards was synonymous with football.” (41) Declaring “the people of the Nail City are football crazy” Barrows went to Pittsburgh looking for opponents. (42)

The four Edwards brothers were the cornerstone as the Intelligencer later gushed: “probably nowhere in the country could one find a single family that produced an equal number of such brilliant players, and for many years the name Edwards was synonymous with football.” (41) Declaring “the people of the Nail City are football crazy” Barrows went to Pittsburgh looking for opponents. (42)

Led by full back Bob Edwards and his brother John at half back, Barrows’s squad backed up his bold talk, defeating the strong Martins Ferry Vigilants 12-6, then “whitewashing” the Pittsburgh based Nonpareils 19-0 (43), and shutting out Western University of Pennsylvania 12-0 in the mud at the Island Fair Grounds. (44) The big contest, with a $200 purse at stake, was to be a rematch with the Vigilants of Martins Ferry, seemingly the uncrowned champions of local football.

Unfortunately, the contest at the Fair Grounds was disrupted by the encroachment of some of the 800 “Enthusiastic Rooters” and the umpire called the game after about an hour, with the only touchdown being disallowed due to crowd interference. “It was a treat for the so-called lovers of the manly art,” The Register reported. “Tumbling, jostling, and rushing, alternating with mastications of the proverbial cloth; unwilling baths in pools of liquid mud; long-winded and ill-natured wrangling over decisions; hooting and yelling and tin horn blowing by enthusiastic rooters, and finally an encroachment on the field which made it impossible to finish the contest.” (45)

Unfortunately, the contest at the Fair Grounds was disrupted by the encroachment of some of the 800 “Enthusiastic Rooters” and the umpire called the game after about an hour, with the only touchdown being disallowed due to crowd interference. “It was a treat for the so-called lovers of the manly art,” The Register reported. “Tumbling, jostling, and rushing, alternating with mastications of the proverbial cloth; unwilling baths in pools of liquid mud; long-winded and ill-natured wrangling over decisions; hooting and yelling and tin horn blowing by enthusiastic rooters, and finally an encroachment on the field which made it impossible to finish the contest.” (45)

Of course, both sides claimed victory. As the teams met to negotiate a rematch, the Vigilants demanded higher stakes of $500 and the teams argued over the costs of a police presence to keep the peace. Ultimately, a rematch could not be arranged. (46)

Of course, both sides claimed victory. As the teams met to negotiate a rematch, the Vigilants demanded higher stakes of $500 and the teams argued over the costs of a police presence to keep the peace. Ultimately, a rematch could not be arranged. (46)

In 1896, The Wheeling Tigers defeated the powerful Western University of Pennsylvania 11-6 (47), and in 1899, impressively defeated Bethany College twice: 6-0 and 12-6. (48) But by the turn of the century, the Tigers, Wheeling’s first powerhouse sandlot football team, had essentially folded, with several of their best players signing with other local squads. During this period high school football, led by Linsly, Wheeling High, Cathedral (later Central), along with some business schools like Elliott, filled the Valley’s football void.

By 1905, the year of the national “Death Harvest,” it seems football had fallen out of favor in Wheeling, prompting a letter to the Register editor headlined, “Why is Wheeling Dead to Football” and signed “A Foot Ball Fan,” who asked why there was no representative team in the city. He admitted the game was “a little rough,” but claimed he’d never witnessed a serious injury. He then called for the Wheeling Tigers to be reorganized so that Wheeling people would “know that we are more than mere weaklings on the face of the earth.” (49)

By 1905, the year of the national “Death Harvest,” it seems football had fallen out of favor in Wheeling, prompting a letter to the Register editor headlined, “Why is Wheeling Dead to Football” and signed “A Foot Ball Fan,” who asked why there was no representative team in the city. He admitted the game was “a little rough,” but claimed he’d never witnessed a serious injury. He then called for the Wheeling Tigers to be reorganized so that Wheeling people would “know that we are more than mere weaklings on the face of the earth.” (49)

As if in answer to this challenge, a few weeks later, Robert Edwards announced his intention to bring back the old Wheeling Tigers to play for the “Ohio Valley Championship.” (50) In their first game as a reunited team, the Tigers went down to defeat 10-0 against New Martinsville, then defeated Benwood 5-0. (51)

Despite Wheeling’s diminished interest, teams had formed all over the remainder of the Valley between 1905 and 1909, from Steubenville to Martins Ferry (Welsh Lads and Indians), Aetnaville, Wheeling Island (Madisons), Bellaire (Globes), South Wheeling (Ritchies), Benwood, McMechen (Tigers), Moundsville (Shamrocks and Independents), and New Martinsville, and nearly all of them at one point or another claimed to be playing for the mythic, “Championship of the Ohio Valley.”

Despite Wheeling’s diminished interest, teams had formed all over the remainder of the Valley between 1905 and 1909, from Steubenville to Martins Ferry (Welsh Lads and Indians), Aetnaville, Wheeling Island (Madisons), Bellaire (Globes), South Wheeling (Ritchies), Benwood, McMechen (Tigers), Moundsville (Shamrocks and Independents), and New Martinsville, and nearly all of them at one point or another claimed to be playing for the mythic, “Championship of the Ohio Valley.”

They played on fields with ominous names like The Loop, Gilchrist Park, the Fair Grounds, League Park, the 47th Street Ground, or the Hell Grounds in Benwood.

Nearly 2,000 people assembled at “The Loop” in 1905 to watch Benwood defeat the Bellaire Globes 39-0. During the game “Zoeckler of Bellaire fell over a stump and was unconscious for some time.” It was “considered remarkable that he was not killed.” (52)

Benwood went on to defeat Steubenville 11-0 and the Island Madisons 10-0 and looked like the team to beat. But when Mound City, featuring former Wheeling Tigers star end Sol Edwards, was defeated 6-0 by New Martinsville, the latter then claimed the “Ohio Valley Championship” for itself. Since they also defeated, a month later, the Wheeling Tigers featuring Sol reunited with his two Edwards brothers, the claim seemed legit. (53)

In 1906, the Moundsville Shamrocks claimed they were vying for the title against the North End Athletic Club, but the North Enders won 6-4. (54) And in 1907, the Welsh Lads of Ferry defeated the Bellaire P.A.C. 10-0 after the latter refused to play the final minute of the game over a disputed umpire’s call. (55)

In 1908, the Glen Lawn (Fulton) Tigers, who claimed the championship, lost to the Martins Ferry Indians on Thanksgiving Day, 6-0 on the Mill Field Grounds. No word was typed as to whether that made Ferry the champs. (56)

Of course, one way to claim a championship was to qualify it by weight class. Teams might be the 115 lb champs or the 140 lb champs, or the 175 lb champs, which seemed to be the heaviest. There were junior versions of many teams, and those might also claim to be champions. The high school championship operated in much the same way. All was by “claim.” And countless games seemed to end in 0-0 ties.

The early Valley football world was a confusing, unregulated, anarchical football wilderness.

In 1909, a new football powerhouse emerged and would become one of the strongest teams to evolve from the Wheeling sandlots.

Playing under the title “Staats A.C.” in honor of their founder and benefactor, Dr. O.M. Staats, the team defeated the strong Glen Lawn squad 11-0 that year. (57)

In a 1913 retrospective about local sports, the Intelligencer hailed Dr. Staats as “the man who has kept football alive in Wheeling” by endeavoring to give the “sporting public of Wheeling … a quality of football that would compare favorably to any in the country.” (58)

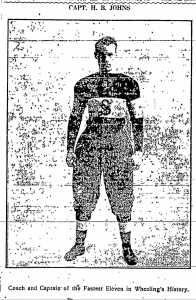

The Staats were lauded for scheduling, and frequently defeating, local college teams under the guidance of player/coach H. B. Johns, who was credited with whipping the team into “an almost perfect football machine.”(59)

The Staats were lauded for scheduling, and frequently defeating, local college teams under the guidance of player/coach H. B. Johns, who was credited with whipping the team into “an almost perfect football machine.”(59)

By the end of the 1913 season, the Register was thanking Dr. Staats for saving football in Wheeling and begging him to keep the team going in spite of the financial losses he’d taken that year due to foul weather and a breach of contract by West Virginia University. (60) According to the Nov. 20 Register, Staats management had received official notice that WVU would not be fulfilling their contract to play Staats the following Saturday. “Local fans,” the Register claimed, “including scores of WVU alumnae find it difficult to restrain their feelings and cries of ‘yellow’ are generally being heard.”

By the end of the 1913 season, the Register was thanking Dr. Staats for saving football in Wheeling and begging him to keep the team going in spite of the financial losses he’d taken that year due to foul weather and a breach of contract by West Virginia University. (60) According to the Nov. 20 Register, Staats management had received official notice that WVU would not be fulfilling their contract to play Staats the following Saturday. “Local fans,” the Register claimed, “including scores of WVU alumnae find it difficult to restrain their feelings and cries of ‘yellow’ are generally being heard.”

But the vitriol did not stop there. In addition to fan disgust, a Staats official was quoted as calling WVU’s tactics, “cowardly.” One “excuse” offered by WVU players was that the game was too close to final exam time, an issue that could easily have been foreseen. These “kindergarten school methods” were said to be “disgracing the name of the state university.”

But the vitriol did not stop there. In addition to fan disgust, a Staats official was quoted as calling WVU’s tactics, “cowardly.” One “excuse” offered by WVU players was that the game was too close to final exam time, an issue that could easily have been foreseen. These “kindergarten school methods” were said to be “disgracing the name of the state university.”

The bottom line was that Staats management lost a ton of money on the breach in reimbursed ticket sales and promotional expenses, and the Staats juggernaut came to an end. (61)

On November 20, 1915, two years after the Staats team folded, Wheeling High School football captain William H. Parker, died after being carried from the field midway through a game at Buckhannon that would determine the state championship.

According to the attending physician, Parker died from a ruptured blood vessel in the brain caused by “over-exertion.” Both schools canceled the final game of the season. For Wheeling, that meant the annual Thanksgiving “Big Classic” against Bellaire. (62)

Wheeling High School’s football club suffered another tragic loss in 1916, when Captain Lee Ritz was murdered. Read the full story, “The Murder of a Football Hero,” on ArchivingWheeling.org.

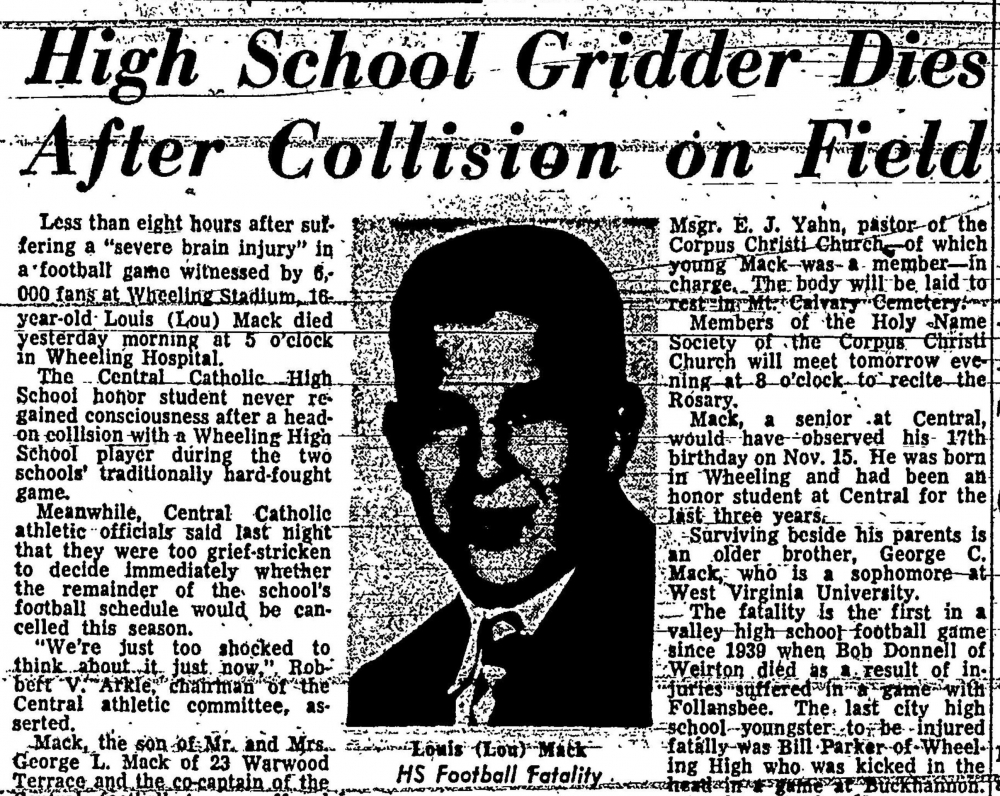

Four and a half decades later on September 21, 1956, sixteen-year old honor student and Wheeling Central tackle and co-captain Lou Mack of Warwood, suffered a “severe brain injury” after a head-on collision with the fullback from rival Wheeling High. Mack died a few hours later at Wheeling Hospital. The school named an annual football award in his memory. (63)

Four and a half decades later on September 21, 1956, sixteen-year old honor student and Wheeling Central tackle and co-captain Lou Mack of Warwood, suffered a “severe brain injury” after a head-on collision with the fullback from rival Wheeling High. Mack died a few hours later at Wheeling Hospital. The school named an annual football award in his memory. (63)

Parker wore a leather helmet. Mack wore a “modern” plastic helmet designed to be safer. But despite four decades of helmet evolution, the result was the same.

Still reeling from the 1920 football-related death of beloved teammate, George Havercamp (see above), the Columbia A.C. squad came back determined in 1921, training in September at a camp along Big Wheeling Creek. (64)

The team consisted of an array of scrappy, talented players like tackle “Buck” Howley (uncle of future Pro Football Hall of Fame linebacker Chuck Howley), quarterback and captain Herb Breiding, left halfback Dubie Dailer, left end Clem Lineweber, and right guard Warren Pugh (a future member of the Wheeling Hall of Fame for his stellar officiating career). The coaches were Guy Morrison and Lou Strotman. (65)

In impressive succession, the Columbias defeated the Toronto Tigers, Mound City American Legion, Benwood A.C, and Warwood Independents (the latter on Halloween, in front of a crowd of 2,000 people, 26-0). (66)

By November, the Columbias (average weight 157 lbs per man) were training for the biggest game of all at Tunnel Green against the rising powerhouse East End Yankees (average weight 156 lbs per man) that would determine the “City Championship.” (67)

By November, the Columbias (average weight 157 lbs per man) were training for the biggest game of all at Tunnel Green against the rising powerhouse East End Yankees (average weight 156 lbs per man) that would determine the “City Championship.” (67)

Sadly, as often happened in those days, the two teams battled to a not so thrilling 0 to 0 tie, though the Register headline maintained that it was in fact a “Thrilling Encounter,” and the Intelligencer went a step further, proclaiming it “the best and most thrilling grid clash ever staged on the Tunnel Green. (68)

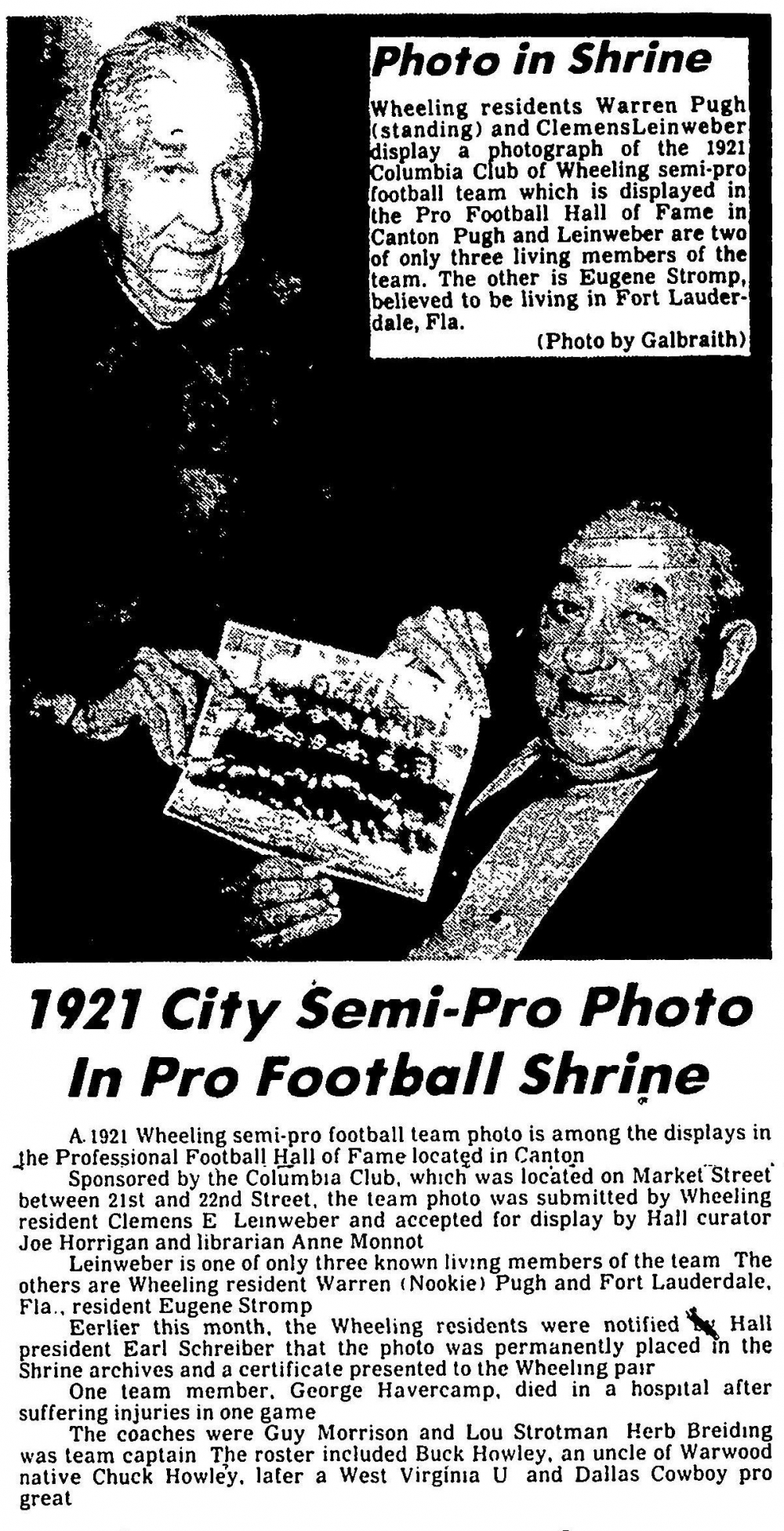

Though the city championship remained “hung in the balance,” the Columbias came close to scoring a few times while the Yankees never did. Perhaps this was enough for the Columbia Club to write “1921 Wheeling Ohio Valley Champions” at the bottom their team photo (which was apparently taken the morning of the rematch with the Yankees and now resides at the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton Ohio – more to come on that), but it wasn’t the full story. (69)

In early December, a rematch was heralded: “This engagement will see the drawing of the gridiron curtain in the Wheeling district, whether it’s a win, loss, or draw contest, and doubtlessly one of the largest crowds ever to assemble on League Park for an independent game will be on hand tomorrow.” (70)

The Sunday Register called the game “an attraction of the queen’s taste,” that was sure to have a “bumper turnout.” The Register also cryptically referred to the East Wheeling Yankees as the “Orangemen,” perhaps to hype the stakes by introducing a sectarian element of Protestants versus Columbia Club Catholics. (71)

The December 12 rematch featured two touchdown passes to “Orangeman” West, combined with bad punting by the Columbias. Final score: Yankees 13, Columbias 0.

Despite the claim on their team photo, the Columbia Club apparently did not actually win the 1921 City Championship. Bubble burst, 104 years later. Sometimes, in the old days before hard and fast rulemaking bodies, a championship “claim” was just that. (72)

Interestingly, in 1979, two of the last three living members of the Columbia Club A. C., Clem Leinweber and Warren Pugh, submitted a copy of their 1921 team photo with the championship claim on it to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton. Where it was placed among the displays. (73)

Interestingly, in 1979, two of the last three living members of the Columbia Club A. C., Clem Leinweber and Warren Pugh, submitted a copy of their 1921 team photo with the championship claim on it to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton. Where it was placed among the displays. (73)

The East End Yankees continued their dominance the next season, again defeating Columbia Club on two occasions by the same score of 13-0.

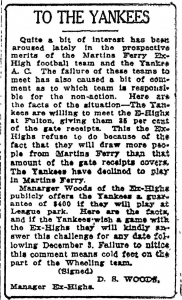

In fact, the Yankees were 8-0 and scored upon only once when they received a challenge from a group of ex high school football players from Martins Ferry. (74) D.S. Woods, manager of the Martins Ferry Ex-Highs placed a challenge in the Nov. 20, 1922 Intelligencer, which read, in part: “Manager Woods of the Ex-Highs publicly offers the Yankees $400 if they will play at League Park. Here are the facts, and if the Yankees wish a game with the Ex-Highs they will kindly answer this challenge for any date following Dec. 3. Failure to notice this comment means cold feet on the part of the Wheeling team.” (75)

In fact, the Yankees were 8-0 and scored upon only once when they received a challenge from a group of ex high school football players from Martins Ferry. (74) D.S. Woods, manager of the Martins Ferry Ex-Highs placed a challenge in the Nov. 20, 1922 Intelligencer, which read, in part: “Manager Woods of the Ex-Highs publicly offers the Yankees $400 if they will play at League Park. Here are the facts, and if the Yankees wish a game with the Ex-Highs they will kindly answer this challenge for any date following Dec. 3. Failure to notice this comment means cold feet on the part of the Wheeling team.” (75)

The challenge was accepted and the Ex-Highs defeated the Yankees for the mythical Valley Championship, 6-0 on a 5 yard first quarter TD run by Paden before a crowd of 7,000 enthusiastic fans at League Park. (76)

Wheeling’s version of Sandlot Football grew in popularity and continued into the late 1920s when the Intelligencer named a regular “Sandlot Football Editor,” Bill Seidel, Jr., who cranked out a regular column alternately title, “Sandlot Musings” or “Following Sandlot Grid Teams.” (77)

Wheeling’s version of Sandlot Football grew in popularity and continued into the late 1920s when the Intelligencer named a regular “Sandlot Football Editor,” Bill Seidel, Jr., who cranked out a regular column alternately title, “Sandlot Musings” or “Following Sandlot Grid Teams.” (77)

In 1929, Seidel wrote about the clash between the undefeated Moundsville Eagles and the undefeated and unscored upon Benwood Bearcats, won by the latter 21-0. (78) In the title match that year, the Bellaire-based Temple Ex-Highs went to the air to become the first and only teams to score on the Bearcats that season, winning 6-0. (79)

By the early 1930s the Bellaire Eagles were the dominant local team, defeating the City Taxies 26-0 in 1931 with the proceeds going to the Knute Rockne Memorial Fund. Rockne, the famous Notre Dame football coach, had been killed in a Kansas plane crash the prior March with Wheeling grocer Charles A. Robrecht also on board. (80) (See “A Crash of Coincidences").

[Photo credit: Art Rooney signed football team photo, 1920s. Greg Ficery Papers and Photographs, 1899-1983, 2009.0062, Detre Library and Archives, Heinz History Center.]

Several years earlier in 1926, a Pittsburgh man named Art Rooney and his brother Dan left the Wheeling Stogies Baseball club, for which they had played the 1925 season, to focus on their own sandlot football team.

Originally known as the “Hope Harveys,” the team was later named the “Majestic Radios” when sponsored by an electronics store. Still later they became the James P. Rooneys to support Art’s brother’s political career.

The team played a few games locally. (81) In 1932, then playing ball as the J.P. Rooneys, the team (referred to in the Intelligencer as “… the Pittsburgh District’s greatest professional football team …”) played and defeated the aforementioned Bellaire Eagles 6-0 in front of 1500 fans in a “rough and tumble” match at Riverview.

Bellaire disputed the result after its two touchdowns were disallowed. The “official had to be escorted from the field by police.” the newspaper reported, “The decision[s] of the game were among the worst ever witnessed in the Valley and were undoubtedly the most biased and prejudiced ever meted out to either a home or visiting team in organized professional ranks.” (82)

The Rooneys, featuring college players from Pitt and Carnegie Tech, had been reportedly undefeated for three years coming into the game. (83) For their part, the Bellaire Eagles, featuring college stars of their own, were said to be the strongest Valley team since Staats A.C. folded. (84)

By 1933, the J.P. Rooneys were reborn under the name “Pirates” and began playing in the National Football League after Art purchased a franchise. (85) By 1940, they were known as the Pittsburgh Steelers.

Regional fans would soon have a new brand of professional football to hold their interest.

From the last 19th Century to the tragic death of George Havercamp, Ohio Valley amateur and semi-professional football mirrored the national game in its level of violence and anarchy.

As rules and equipment evolved to improve player safety, the game’s popularity fluctuated, yet persistently overtook that of baseball. Eventually, every town and village had a team, from Weirton to Warwood, and from East Wheeling to New Martinville in West Virginia, and from Steubenville to Shadyside in Ohio.

Local semi-pro teams regularly played college teams, and championship claims were abundant and often conflicting. And this is only half of the sometimes uplifting, sometimes frightening, often tragic and always intriguing story of Ohio Valley football.

The research revealed enough information to justify a second installment that will carry the pigskin forward from the World War era to the rise of the Wheeling Ironmen.

1 “Injured in Football Game.” (1920, Sept. 27). Wheeling Intelligencer (WI), p. 8.

2 “Olympic Open with Columbias.” (1920, Sept. 14). Wheeling Register (WR), p. 8.

3 “George Havercamp May Die as a Result of Football Game.” (1920, Sept. 29). WI, p.3; “Football Player in Serious Condition.” (1920, Sept. 29). WR, p. 7.

4 “George Havercamp Succumbs to Injuries in Football Game.” (1920, Oct. 1) WI, p.10.

5 “Havercamp Obsequies.” (1920, Oct. 3). WR, p. 3.; “Geo. Havercamp Buried Monday.” (1920, Oct. 2). WI, p. 13.

6 WI, Oct. 1, 1920, p. 10.

7 “1st college football game ever was New Jersey vs. Rutgers in 1869.” NCAA.com. Online: https://www.ncaa.com/news/football/article/2017-11-06/college-football-history-heres-when-1st-game-was-played

8 “1869 to 1890: How American Football Became (The Game You Love Today) - College Football History.” Corn Nation. Online: https://youtu.be/OEEtsbOlCBU?si=v1eq_EvDfNvKtlnd

9 Weinreb, M. “Harvard vs. McGill set the stage for the growth of college football as we know it.” NY Times. Jan. 28, 2019 Updated June 13, 2019. Online: https://www.nytimes.com/athletic/785894/2019/01/28/harvard-mcgill-1874-series-college-football-history/

10 “The Father of American Football.” College Football Hall of Fame. Online: https://www.cfbhall.com/news-and-happenings/blog/the-father-of-american-football/.

11 “Yale's Walter Camp and 1870s Rugby.” Ivy Rugby Conference. Online: https://www.ivyrugby.com/news/yales-walter-camp-and-1870s-rugby

12 “1869 to 1890: How American Football Became (The Game You Love Today) - College Football History.” Corn Nation. Online: https://youtu.be/OEEtsbOlCBU?si=v1eq_EvDfNvKtlnd

13 Ibid.

14 Johnston, J. “1884-1894: Mass Momentum Plays and Brutality Bring Football to Edge of Extinction.” Corn Nation. Online: https://youtu.be/c28x5EY4tLY?si=WDVNahLhZhH81iUh

15 Dujack. S. “Woodrow Wilson ’79’s Role in Football.” Princeton Alumni Weekly. Online: https://paw.princeton.edu/article/woodrow-wilson-79s-role-football

16 Pudge Heffelfinger. National Football Foundation. Online: https://footballfoundation.org/hof_search.aspx?hof=2109; “William Walter ‘Pudge’ Heffelfinger First Professional Football Player.” US Gen. Online: https://www.usgenwebsites.org/TXMatagorda/family_heffelfinger2.htm

17 “Flying Wedge First Used in 1892 by Deland Coached Harvard Team.” The Harvard Crimson. Online: https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1926/11/5/flying-wedge-first-used-in-1892/

18 Johnston, J. “1884-1894: Mass Momentum Plays and Brutality Bring Football to Edge of Extinction.” Corn Nation. Online: https://youtu.be/c28x5EY4tLY?si=WDVNahLhZhH81iUh

19 “Blast from the Past: How Theodore Roosevelt Changed Football.” Football 101. Online: https://fansguidetofootball.wordpress.com/2016/03/20/how-theodore-roosevelt-changed-football/#more-103

20 “Football’s Death Harvest of 1905, or How Teddy Roosevelt Saved the Grid Game.” New England Historical Society. Online: https://newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/footballs-death-harvest-of-1905-or-how-teddy-roosevelt-saved-the-grid-game/

21 “TR Encyclopedia – Culture and Society Football.” Theodore Roosevelt Center. Online: https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/encyclopedia/culture-and-society/football/.

22 “Football’s Deadliest Plays: How the 1909 Crisis Reshaped the Game Forever.” Hardcore College Football. Online: https://youtu.be/ZhBJQa4onHs?si=BUMAOFhSu1v_qGKA

23 Opponent History, WVU Sports. Online: https://youtu.be/taS0M1yVOak?si=LGYwVzgmzKeJWpV9

24 “Munk of W.V.U. Dies from Injuries Inflicted in Wheeling Game: Umpire Declares a Bethany Player Deliberately Felled Munk.” Page 1 of Wheeling News Register, November 13th, 1910

25 “Warrant Sworn Out For McCoy, the Bethany Football Player Charging Murder of Rudolph Munk of the W.V.U. Eleven.” Page 1 of Wheeling Daily Register, November 14th, 1910; Phyllis Smith. This Day in History: Nov. 12, 2025. Online: https://www.wtap.com/2025/11/12/this-day-history-nov-12-2025/

26 “Today's Tidbit... Murder On The Football Field?” Oct. 11, 2023. Football Archaeology. Online: https://www.footballarchaeology.com/p/todays-tidbit-murder-on-the-football

27 (Nov. 25th, 1882). Wheeling Daily Intelligencer. p. 4.

28 “The Coming Game.” (1891, Nov. 27). Wheeling Daily Register, p. 4.

29 “Football Contest Yesterday.” (1891, Nov. 27). Wheeling Daily Register, p. 5.

30 “Football Team Bring Organized.” (1893, Dec, 1). Wheeling Daily Register, p. 6.

31 “Thanksgiving Football Game.” (1893, Nov. 26). Wheeling Sunday Register, p 12.

32 “A Very Good Game.” (1893, Oct. 9). Daily Intelligencer, p 3.

33 “The Foot-Ball Game.” (1893, Nov. 30). Wheeling Daily Register, p 5.

34 “Y.M.C.A.’S Are Cracks: Red and White Go Down Before the Lavendar and Black.” (1893, Dec. 1). Wheeling Daily Register, p. 5.

35 Ibid.

36 “Martins Ferry Won.” (1894, Oct. 21). Wheeling Sunday Register, p. 5.

37 Ibid.

38 “Football Hair: By Their Wavy Locks Shall Ye Know Them.” (1894, Nov. 25.). Wheeling Sunday Register, p. 7.

39 Ibid.

40 “Tigers and W.U.P.” (1896, Nov. 26). Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, p. 3.

41 Plummer, R. “Wheeling’s History in the World of Sport: A Brief Review of Both Past and Present Athletic Activities.” (1913, Oct. 31). Wheeling Intelligencer, p. 62.

42 (1895, Sept. 25). Wheeling Daily Register, p. 6.

43 “Nonpareils Shut Out by the Wheeling Tigers by the Score of 19-0.” (1895, Oct. 13). Wheeling Sunday Register, Sunday, p.8.

44 “W.U.P. Failed to Score. The Tigers Won a Decisive Victory Over Pennsylvania Eleven.” (1895, Nov. 25). Wheeling Daily Register, p. 6.

45 “Draw Game of Football. Yesterday Between the Tigers and Martins Ferry Vigilants.” (1895, Dec. 1) Wheeling Sunday Register, p.6.

46 “Yesterday’s Game Between Tigers and Vigilants.” (1895, Dec. 1). Wheeling Sunday Register, p. 3.

47 “Sports. Tigers 11; W.U.P. 6.” (1896, Nov. 27). Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, p. 2.

48 “Wheeling Defeated Bethany In a Brilliant Game Witnessed by a Record Breaking Crowd.” (1899, Dec. 1). Wheeling Daily Register, p. 6.

49 “Why is Wheeling Dead to Football.” (1905, Oct. 7) Wheeling Daily Register, p.6.

50 “Tigers in Field. Old Team of Foot Ball Stars to Reorganize for Championship Battle.” (1905, Oct. 30). Wheeling Daily Register, p. 6.

51 “Tigers Take Game by Close Score from Benwood.” (1905, Nov. 26). Wheeling News Register, on Sunday, p. 13.

52 “Benwood Easily Defeated Globe.” (1905, Sept. 25). Wheeling Intelligencer, p. 7.

53 “New Martinsville Bests Moundsville.” (1905, Oct. 29). Wheeling News Register, p. 13.; “New Martinsville Defeated the Tiger Team.” (1905, Nov. 19). Wheeling News Register, p. 13.

54 “Moundsville Loses to North Enders in Fast Game.” (1906, Nov. 30). Wheeling Daily Register, p. 7.

55 “Disagreement. Welsh Lads and P.A.C. Quit with One Minute to Play.” (1907, Nov. 29). Wheeling Daily Register, p. 9.

56 “Indians Won.” (1908, Nov. 25). Wheeling Daily Register, p.6.

57 “Staats Athletic Club Add Another Victory.” (1909, Nov. 22). Wheeling Intelligencer, p. 7.

58 Plummer, R. “Wheeling’s History in the World of Sport: A Brief Review of Both Past and Present Athletic Activities.” (1913, Oct. 31). Wheeling Intelligencer, p. 62.

59 Ibid.

60 “Is Wheeling to Drop from Grid Irin Sport Forever?” (1913, Dec. 9). Wheeling Intelligencer. p.7.

61 “W.V.U. Will Not Play the Staats.” (1913, Nov. 20). Wheeling Daily Register, p. 9.

62 “Captain Parker of High School Football Team Meets Death in Game.” (1915, Nov. 21). Sunday Register, p. 1.

63 “Central Grid Star Critical After Game.” (1956, Sept. 22). Wheeling Intelligencer, p. 1.;”High School Gridder Dies After Collision on Field.” (1956, Sept. 23). Wheeling News-Register, p. 1.

64 “Columbia Club.” (1921, Sept. 26). Wheeling Register, p. 6.

65 Photograph of the 1921 Columbia Club football team with names listed. Archives of the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston.

66 “Columbia 26, Warwood 0.” (1921, Oct. 31). Wheeling Intelligencer, p. 6.

67 “Yankees Meet Columbia A.C. All Important Clash is Scheduled for Tunnel Green Tomorrow Afternoon.” (1921, Nov. 19). Wheeling Intelligencer, p. 7.

68 “Yankees Play Columbia 0-0.” (1921, Nov. 21). Wheeling Intelligencer, p. 9.

69 “Columbias Battle Yankees to 0-0 Tie in Thrilling Encounter. South Side Aggregation Outplays East End Aggregation, But Could Not Score.” (1921, Nov. 21). Wheeling Register, p.8.

70 “Columbia A.C. Meet Yankees.” (1921, Dec. 10). Wheeling Intelligencer, p. 7.

71 “Columbias Meet Yankees Today.” (1921, Dec. 4). Wheeling Sunday Register, p. 16.

72 “Yankees Battle Columbia 13-0. Now Claim Championship of City of Their Class--Game Was Hard Fought.” (1921, Dec. 12). Wheeling Register, p. 7.

73 “1921 City Semi-Pro Photo in Pro Football Shrine.” (Jan. 20, 1979). The Intelligencer, p. 22.

74 “Yankee A.C. Close Successful Year.” (1922, Dec. 6). Wheeling Intelligencer, p. 7.

75 “To the Yankees.” (1922, Nov. 20). Wheeling Intelligencer, p. 7.

76 “Ferry Team Wins Exciting Game by a Touchdown, 6-0.” (1922, Dec. 4). Wheeling Register, p. 8.

77 “Sandlot Musings.” (1928, Oct. 8). Wheeling Intelligencer, p. 9.; “Following Sandlot Grid Teams.” (1928, Nov. 24). Wheeling Intelligencer, p. 9.

78 “Bearcats and Eagles Clash.” (1929, Nov. 9). Wheeling Intelligencer, p. 11.; and “Bearcats Defeat Moundsville 21-0.” (1929, Nov. 11). Wheeling Intelligencer, p. 13.

79 “Temples Use Air to Beat Bear Cats for OV Title.” (1929, Nov. 25). Wheeling Register, p. 9.

80 “Eagles Defeat City Taxi Team.” (1931, Nov. 16). Wheeling Register, p. 10.

81 “Steubenville Beats Fort Pitt Bull Dogs.” (1926, Oct. 11) Wheeling Register, p. 7.

82 “Bellaire Eagles Lose 6-0 Disputed Game to Rooney A.C.” (1932, Oct. 31). Wheeling Intelligencer, p. 9.

83 “College Stars at Bellaire.” (1932, Oct. 19). Wheeling Intelligencer, p. 9.

84 “Eagles Have Strong Team.” (1932, Oct. 27). Wheeling Intelligencer, p. 12.

85 Heinz History Center Facebook page post, July 8, 2025. Online: https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1CpqVFiYQX/?mibextid=wwXIfr

© Copyright 2026 Ohio County Public Library. All Rights Reserved. Website design by TSG. Powered by SmartSite.biz.